Client

: Personal Folio Piece.

Medium

: Pencil

Sketch (on

Cartridge) 20cm by

28cm :

Coloured and Enhanced in Adobe

Photoshop 2008 a.d

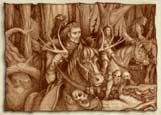

Notes : I've

had a few queries concerning the nature of this sketch,

Its a rendering of a Scythian belt

plaque The original is made of gold with turquoise

inlays, (width:

15.24 cm height: 9.35cm) circa 3rd century

B.C. from Altay, currently held in Czar Peter

I's (Пётр

Алексе́евич Рома́нов ) Siberian collection,

stored at the Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

The buckle portrays a yak biting a snow leopard which

in turn is shredding the tail feathers of a really

big eagle who is tearing chunks out of the yak's neck.

There may be a mirrored version of this plaque (Attached

to the other end of the belt ).

One of the Clients

I previously worked with afforded

a great deal of interaction with jewellery

making. Part of that job involves a lot of photo

retouching and rendering the appearance of gold

and other precious metals. The illustration above

comes off as a a very rosy gold and the turquoise

needs more of a matte finish.

Gold

itself, in its pure form is 24 carats, it is a soft

metal, much like lead, on Mohs scale of hardness,

gold has a hardness value of 2 to 2.5. Diamond has

a value of 10. Humanity has found that in order to

make more durable jewellery, gold needs to be mixed

with harder metals. This is the reason jewellery is

not made in pure gold, it comes in 18 carats, 14

carats and 10 carats.

|

Notes on Scythians and their Culture :

Scythian Artisans

worked with a diverse range of decorative materials such

as gold ( being the most unifying aspect of Scythian

art as mentioned above), wood, leather, finely

carved bone (retrieved from Glittering çapraks

- saddlecloths often made of goatskin),

bronze (mirrors and pole topes), iron, silver (utensils),

electrum and of course the extraordinary tattoos.

All

this from what has been extracted out of archaeological

excavations or pillaged from the Scythian

kurgans (burial mounds, for you Highlander

fans). It begs the

question has a far greater level of artwork been

lost to us through the greed and plundering

of the last 2 centuries ( as Herodotus mentions

the Scythians made everything out

of copper and gold ).

By

the fourth century BC Scythian bridle

trappings found in burials

of the northern steppe zone

beyond the Black Sea (referring

to present day Ukrainian and Russian lands approx. north of

the 48' parallel) reflected a determined adoption of the Thracian tendency

to treat decorative objects in terms of flat, incised surfaces

whereby established motifs such as Griffin (or Gryphon,

a creature said to inhabit the Scythian steppes) heads,

wings and feathering, were stylised into simplified yet easily

recognizable forms.

There are several arguments mustered in support of the attribution

of near Eastern and Greek craftsmanship

for the best and finest of Scythian metalwork.

There is, to begin, the assumption that Scythians did

not have a clue how to cast gold before they came into contact

with West Asian traditions. According to this line of reasoning,

it was the Persian love of solid gold and

the Greek sophistication in the working of

this precious metal that attracted the Scythians attention

to the possibilities inherent in solid gold or in such metal

techniques as filigree and granulation. This supposition needs

to be carefully qualified as the archaeological context is

extremely fragmented.

As prosperity increased among the Scythians through

trade with the Greeks, their nomadic lifestyle

waned as more and more of the tribes settled down to a more

rural existence. Permanent settlements began to spring up with

greater frequency along the archeological record, such as the

Bilske Horodyshche, a

dig in

the Poltava

Region of the Ukraine near

Belsk, that

gave up an ancient metropolis (1000 times larger

than Troy) believed

by Boris

Shramko to be Gelonus,

the Scythian

capital (discussed

by Herodotus), craft workshops and Greek pottery

captured the attention of those excavating the immense

ruin. Exquisite Felt appliqué wall

hangings survive within the archaic catacombs

at Pazryzk displaying

fine artwork acknowledging their Great Goddess or exhibiting

the stylised actions of Scythia's distinct anthropomorphic

beasts. Further decorations demonstrate well conceived geometric

motifs that predate the celts beautiful designs. Archaeologists

have also uncovered felt rugs, well crafted tools and domestic

utensils. Clothing uncovered by archaeologists has also been

well made many trimmed by embroidery and appliqué designs.

Wealthy people wore clothes covered by gold embossed plaques.

Animalia appears to

be the primary subject matter among Scythian jewellers.

From what we have retrieved from the earth focuses on stags,

mountain lions, predatory birds, horses, bears, wolves and

what has been deemed by the intelligentsia as 'mythical'

beasts, for example Gryphons (γρυψ)

: widely depicted throughout ancient Greece*,

mostly on coins or as paintings or sculptures to impart good

luck. The earliest depictions come out of Crete, where Gryphons

were usually shown as royal animals and guardians of throne

rooms. Again the intelligentsia postulate that The Scythians used

petrified bones found in and about their steppes as proof of

the existence of Gryphons 'attributing

a level of gullabilty to the ancients that appears common

among the scientific communities meme'.

It has been suggested that these

"Gryphon bones" were Protoceratops fossils (predecessor

of the more familiar horned dinosaurs such as Triceratops),

which are common in that part of the world.

The vigour of stylizations

shown in the golden figures of stags in their reclining poses

is astonishing, These were often the central ornaments

for shields carried by fighters. In the most notable of these

figures, stags are displayed with legs tucked beneath its body,

head upright and muscles tight to give an impression of movement

or life.

Archaeology

:

The earliest archaeological discoveries in southern Siberia

date from the beginning of the 18th century. Nicolaas Cornelius

Witsen (dutch embassy: Moscow) received 2 consignments of objects

in 1714 and 1716 consisting of forty gold articles, including

neck rings (grivny) of the finest workmanship, belt plaques

and other ornaments adorned with the now distinctive animal

motifs. Witsen's collection survives today only as fine sketches

within the pages of his book Nord en Oost Tartarie. Upon

Witsen's death the artifacts were sold at auction and melted

down for their base pecuniary value. During the same time period,

Nikita Demidov, presented the empress Yekaterina

(Catherine) with "precious gold objects from

Siberian tombs" These

works (as well as over 100 pieces relayed by Prince Gagarin,

the then governor of Siberia) formed the foundation of the

collection held by the Hermitage

Museum in Saint

Petersburg. Catherine the Great was

so impressed from the material recovered from the kurgans that

she ordered a systematic study be made of the works. Reports

of local officers began to contain reference to the discovery

of ancient objects and the wholesale ransacking of kurgans

by grave robbers and brigands.

One of the first sites

discovered by modern archaeologists were the kurgans Pazyryk, Ulagan district

of the Altay Republic (Алтай

Республика),

south of Novosibirsk. The name Pazyryk culture

was Attached to the finds, five large burial mounds and several

smaller ones between 1925 and 1949 opened in 1947 by a Russian

archeologist, Sergei Rudenko; Pazyryk is

in the Altay Mountains of southern Siberia.

The kurgans contained items for use in the afterlife. The

famous Pazyryk carpet discovered is the

oldest surviving wool pile oriental rug.

A kurgan near the village of Ryzhanovka in

the Ukraine, 75 miles south of Kyiv,

found in the 1990's has revealed one of the few unlooted tombs

of a Scythian chieftain, who was ruling in

the forest-steppe area of the

western fringe of Scythian lands. There at a late date

in Scythian culture (ca. 250 - 225 BC), a recently

nomadic aristocratic class was gradually adopting the agricultural

life-style of their subjects. Many items of jewellery were

also found in the kurgan.

A discovery made by Russian

and German archaeologists in 2001 near Kyzyl,

the capital of the Russian republic of Tuva in Siberia is

the earliest of its kind and predates the influence of Greek civilisation.

Archaeologists discovered almost 5,000 decorative gold pieces

including earrings, pendants and beads. The pieces contain

representations of many local animals from the period including

panthers, lions, bears and deer.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Ancient

Greeks believed in the Gigantes (Γίγαντες)—Titans,

heroes and semi-human creatures far larger

than what would be now be considered the

norm. Atlas, the Cyclops, and the Titans

were among them, but possibly the greatest

of them all was Pelops. Poets envisioned

him as a handsome interloper from the east,

with a shoulder blade made of ivory (after

having a vegetarian Goddess inadvertently

eat his shoulder). After winning a rigged

chariot race, Pelops was said to have founded

the Olympic games as a way to honour the

gods for his victory. He also reigned over

Greece's southern peninsula—the Peloponnese,

whose name means "Pelops's island."

At the peninsula's northwest corner stood Olympia,

a religious complex that was the site of the Olympic games

and of a shrine that claimed a relic of the mighty giant himself—his

massive, ivory-white shoulder blade. During the Trojan War,

the elephantine relic was reportedly shipped to the walls of Troy,

as a talisman to bring the Greeks victory.

Greek writers, from the fifth-century B.C.

historian Herodotus to

the second-century A.D. travel writer Pausanias,

chronicled sightings of the remains of giants. Immense, disarticulated

skeletons appeared along unstable shorelines, and huge, jumbled

bones poked from weathered hills and cliffs.

Today most if not all 'scholars' shelve stories of giant

bones under fiction ( because ancient writers were

stupid, and didn't have the proper institutions to tell

them what to think and pretty much just pulled ideas out

of their arses- creative thought is bad).

But Adrienne Mayor, a folklorist and historian

of early science, takes the Greeks at their word. "Since

the 19th century," Mayor says, "modern paleontologists

have discovered rich bone beds of giant, extinct mammals in

the same places the ancient Greeks reported finding the bones

of heroes and giants." She thinks what the Greeks actually

found were isolated fossil bones of creatures like the southern

mammoth. With no other way to explain the bones, the Greeks,

being ignorant (as all ancient races would have to have

been), conceived them as the porous calcified remnants

of giant god-like characters.

In theory Mammoth bones would have dwarfed

any living creature native to the lands of

the ancient Greeks. The fossil beds that

studded the Greek and larger Mediterranean

world included those of Mammoths, Elephants,

and other animals that had lived tens of

thousands of years before the Greeks. More

fragile bones, such as skulls, often didn't

survive. But denser remains—shoulder

blades and thighbones, which bear a resemblance to human bones—did.

"They also found fossil ivory tusks from extinct mammoths

in the ground," Mayor says, "and they (must have)

assumed the ivory was produced by the earth, like gems and

minerals. In fact, the ancient Greek word for ivory, elephas,

was the name they gave to elephants once they did encounter

them." That first encounter probably didn't happen until

the fourth century B.C., when Alexander the Great and his army

advanced on Babylon and were met by a phalanx of Persian war

elephants.

By that time, though, the myths of superhumans

and giants were well established in the Greek

mind. Could some of these characters have

been inspired by finds of enormous fossil

bones that couldn't otherwise be explained?

Or did the myths come first—and

when confronted with the bones, did the Greeks imagine them

reassembled as the villains and heroes of the larger-than-life

mythic world?

Personal

Library :

Recommended Reading : ( links to Amazon.com

if available)

The

Art of the Scythians: The Interpretation of Cultures at the

Edge of the Hellenic World (Handbook of Oriental Studies,

Vol 2) (Hardcover) Esther

Jacobson(-Tepfer) Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1995. (Hardcover) Esther

Jacobson(-Tepfer) Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1995.

The

Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe (Hardcover)

Oxford Barry

Cunliffe (Editor) University Press, USA (May 12,

1994) (Hardcover)

Oxford Barry

Cunliffe (Editor) University Press, USA (May 12,

1994)

The

Story of Archaeology: The 100 Great Archaeological

Discoveries Paul

G. Bahn (editor) Phoenix (an Imprint of The Orion Publishing

Group); New Ed edition (1997) Paul

G. Bahn (editor) Phoenix (an Imprint of The Orion Publishing

Group); New Ed edition (1997)

The

Scythians (Ancient

peoples and places. 2) (Hardcover)

Tamara Talbot Rice: Thames & Hudson. 1957. (Ancient

peoples and places. 2) (Hardcover)

Tamara Talbot Rice: Thames & Hudson. 1957.

The History of Herodotus.

Trans : George Rawlinson: (Hardcover)

University of Chicago 1952.

Herodotus:

The Histories John

M. Marincola (Editor), Aubrey De Selincourt (Translator)

Penguin Classics (September 1, 1996)

The

Ancient Civilization of South Siberia (Hardcover)

Mikhail Gryaznov : Barrie &

Rockliff, London 1969. (Hardcover)

Mikhail Gryaznov : Barrie &

Rockliff, London 1969.

The

First Horsemen :

The Emergence of Man (Hardcover) Frank Tippet : Time-Life

Books 1974. :

The Emergence of Man (Hardcover) Frank Tippet : Time-Life

Books 1974.

The World's Last Mysteries Reader's Digest Association (January 1978)

Reader's Digest Association (January 1978)

A

History of Russia Nicholas

V. Riasanovsky (Author) Oxford University Press, USA; 5 edition

(March 11, 1993) Nicholas

V. Riasanovsky (Author) Oxford University Press, USA; 5 edition

(March 11, 1993)

The

Archaeology of Ancient Turkey (Bodley Head Archaeology) (Hardcover)

James Mellaart (Author) (April 1978) (Hardcover)

James Mellaart (Author) (April 1978)

Russian

history atlas (Hardcover) Martin

Gilbert (Author) Weidenfeld & Nicolson (1972)

Additional

Reading:

http://www.cannabisculture.com/backissues/cc02/scythians.html

Note to self : Do

not lend books to people , they just don't return

the good ones. |